All pictures were taken by the author during his visit to The Met Fifth Avenue, New York. Texts sourced from exhibit label scripts.

Public Parks

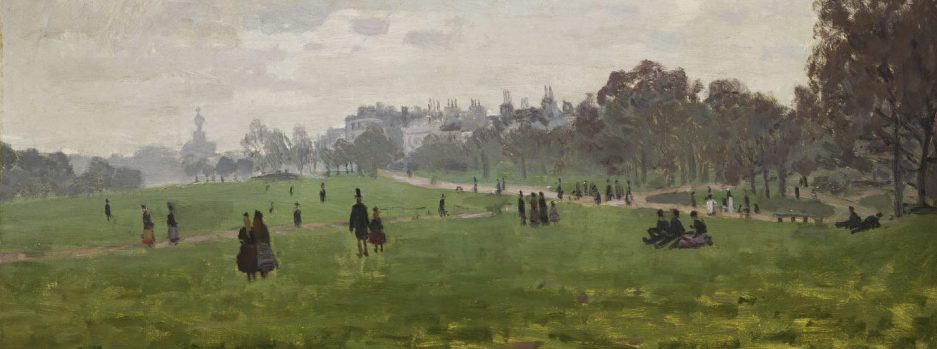

The Parc Monceau in the elegant eighth arrondissement was among the older Parisian parks targeted for renovation and unveiled in 1861. Monet lived a few blocks away from this intimate park. At first he adopted a horizontal format, as in the views he painted of London’s Green Park (1870-71), but for the second group he used a more unusual vertical format, perhaps inspired by Japanese woodcut prints.

Monet takes in the park’s curving paths on a sunny afternoon. He skimmed lightly over the figures of park-goers, blending them in with enveloping vegetation, filling the canvas with little patches of color that approximate the texture of foliage and the flicker of light.

Like Monet, Caillebotte was drawn to the renovated Parc Monceau. He inserted a path the beckon viewers into the picture and a bench to invite them to linger. A solitary Parisian gentleman, achieved with just a few quick strokes, suggests the urbanity of the site.

Later in his career, Pissarro — the least cosmopolitan of the Impressionists — devoted successive painting campaigns to the landscape of modern Paris. In 1899 and 1900, he took leave of his home in rural Eragny to rent a large apartment high above the rue de Rivoli “opposite the Tuileries, with a superb view of the garden”. He painted two series of fourteen views each, including half a dozen from the same vantage point. Attentive to changes in the light and color of the grounds, the relative fullness of the trees, and the comings and goings of strollers at different times and seasons, he extracted the very nature of this site.

Renoir gravitated to more traditional motifs during his later career. In this autumnal view of the courtyard on the north side of the palace of Versailles, he paints the chestnut trees that line the allée in rich seasonal hues, while he accords sculpture a key role.

By the early nineteenth century, virtually every town, large or small, was graced with a promenade or public garden not unlike the one Pissarro painted in Pontoise. In this semi-rural, semi-suburban hamlet just northwest of Paris, a stroll in the park was a social event.

Monet studied the dramatic shapes and shadows formed by one of Fontainebleau’s most frequently painted and photographed trees, the Bodmer Oak, in preparation of his ambitious picture Luncheon on the Grass (1865-66). Using a palette of bright yellows, greens, and oranges to depict sunlight filtering through the trees, Monet painted this autumnal view just before he wrapped his visits to Fontainebleau in October 1865.

Floral Still Lifes

One of Cassatt’s rare still lifes, this painting was presumably made at the country house her family rented outside Paris. She placed her casually arranged bouquet on the windowsill of the greenhouse, close to the open air, in cool spring light.

Monet was praised for the “brio and daring” of his technique when the picture was shown at the 1882 Impressionist exhibition. Such qualities seem to have resonated with Paul Gauguin six years later, when he was even more dazzled by the suite of Sunflowers Van Gogh has painted as a decoration for his room in Arles.

By the summer of 1887, Van Gogh had updated his drab Dutch palette by painting flowers and come into his own as an original colorist. He made the dried blooms and stalks of the tall tournesols the focus of four works, magnifying their ragged heads, where flame-like sepals halo the seed destined to yield next year’s flowers.

Monet painted more than twenty floral still lifes between 1878 and 1883, fixing his sight on generous displays of a single type of flower at the height of bloom as opposed to mixed bouquets. A perennial favorite was the exotic chrysanthemum. In painting the small, pearly mums of late summer with petal-size dabs and dashes, Monet created a shimmering effect that is reflected on the polished tabletop, mirroring his concurrent infatuation with the watery surfaces of the Seine.

Caillebotte did not develop an interest in floral subjects until the 1880s, when he acquired property in the Parisian suburb of Petit-Gennevilliers. He found inspiration enough to shift his focus from urban scenes of bourgeois leisure to his own backyard. In redirecting his gaze to the plants he had nurtured from the ground up — such as this thicket of homegrown chrysanthemums, seen from an intimate and provocative vantage point — he continued to create what one critic hailed as “impromptu views that are the great delights in life.”

Although Degas once expressed his aversion to scented flowers, he nodded to current fashion by portraying a woman seated beside an enormous bouquet of asters, dahlias, and other late-summer blooms. The gardening gloves and water pitcher on the table suggest that the sitter had gathered and arranged flowers from the garden glimpsed through the window.

The extraordinary range of hues in which chrysanthemums could be cultivated caught the eye of Renoir. Probably gathered from the garden of his patron Paul Bérard at Wargemont, in Normandy, they must have emboldened the artist to test his overheated palette. “When I painted flowers,” he said, “I fell free to try out tones and values and worry less about destroying the canvas.”

Attentive to botanical accuracy, Delacroix brought a sense of realism to his works that was soon to become the province of photographers. And for younger painters, he set an influential precedent for how high-key color and freewheeling paint strokes could contribute robust vibrancy to a subject often too daintily treated.

Reportedly Manet’s favorite flower, peonies were introduced to France in the early nineteenth century. They grew in abundance in the artist’s garden in the Parisian suburb of Gennevilliers. Considered the epitome of luxury, the voluptuous flowers were a perfect vehicle for his sensuous brushwork and virtuosic handling of subtle color harmonies.

Private Gardens

During the summers of 1881 to 1884, spent with her family in the village of Bougival, just west of Paris, she often painted the garden of their rental house with its wrought-iron gate, tall hollyhocks, and dense foliage. The figures emerging from the verdant surroundings may be Morisot’s five-year old daughter, Julie, and their maid, Pasie.

Cézanne’s affection for his family’s estate, Jas de Bouffan, near Aix-en-Provence, is reflected in the many views he painted of the property over a quarter century. He pictured this prospect along the road that led from an eighteenth-century house to its landscaped gardens, charting the symmetry of the massive chestnut trees and often including the stone washing trough and large square pool for collecting water. A sense of cool tranquility prevails in the artist’s depictions of the garden that afforded him refuge from the challenges of life in Paris.

Monet was in his twenties when he began to setting up his easel in sunlit gardens. While spending the summer of 1867 with his family on the Normandy coast, he painted his aunt’s garden in the seaside resort of Sainte-Adresse, near the port of Le Havre. The manicured oasis of standard roses and bedding geraniums at her villa made a stunning setting for the artist’s sidelong portrait of his father, Adolphe, a prosperous merchant.

After Monet established his own bourgeois household in rented properties in the Paris suburb of Argenteuil between 1871 and 1876, he began to garden in earnest, making his flower-filled backyards the subject of more than thirty canvases. The artist planted a central flower bed in a walled circular space: gladioli and hollyhocks soar above nasturtiums and geraniums to provide burst of colors at laddered levels, in accord with the current fashion for mounded combinations of annuals and perennials. The hollyhocks grew taller than Monet’s wife, Camille, whose painted from dissolves in shadows, submitting to the primacy of flowers and foliage.

With bemused sunlight, Bonnard pictures here a bucolic summer day at the family estate in Le Grand-Lemps, near Grenoble, adopting a high vantage point that offers a glimpse of five of his offspring and their pets cavorting amid the assorted greenery of vines, shrubs, and trees spread over luxuriant lawns.

Garden Portraits

Manet painted his wife in the sunlit greenery of their seasonal residence in Bellevue. Much of her face is hidden beneath the broad rim of hat, and her figure melds with the background realized in bravura strokes of ocher, blue, and emerald green.

One of Cassatt’s first and most dazzling plein-air pictures, this portrait of her sister Lydia debuted to praise at the 1881 Impressionist exhibition. Lydia is placed along a diagonally receding walkaway, bordered by plants, inviting comparison with Morisot’s somewhat later picture of a sitter absorbed in her knitting. Cassatt rendered her frail sister’s features with sensitivity, using freer brushwork to describe her stylish dress and still more vigorous handling for the foliage of gladioli, roses, and coleus leading to the greenhouse.

In this slice-of-life view, Morisot suspends descriptive detail to create a portrait of her time, making a bold fashion statement of sorts: her sitter sports the latest style of dress and is shown knitting in a garden typical of the period, with a gravel path and flowering roses. The elegant chairs suffice to define the private setting. Morisot probably painted the work in Bougival, where she spent the summers of 1881 to 1884, perhaps enlisting her daughter’s nanny as model.

At the time when artists were churning out sentimental images of women in gardens for the annual Salons, Morisot introduced invention where tired stereotypes left off. She magically transformed the interior into a place out of doors, opening it to her balcony and bringing roses and hydrangeas into the company of a flower-bedecked hat and the floral upholstery of a tufted settee. Her approach led one critic to comment in 1880: “She grinds flower petals onto her palette, in order to spread them later on her canvas with airy, witty touches.”

An echo of suitors in Garden of Love paintings from an earlier era. No less traditional is the presentation of the half-acre walled garden. Yet its bright red zonal geraniums are clustered in a corbeille, a basket-shaped flower bed that had recently become as much a fixture in French parks as the bench. Both the parklike setting and Camille’s smart ensemble ascribe to the latest fashion. Still, the sitter telegraphs sadness amid the sunlit blooms.

During the summer of 1874, Manet paid a visit to the Monet family. Finding them enjoying a leisurely afternoon in their garden, he set up his easel to paint in the open air. Renoir, who arrived just as Manet was starting to work, borrowed materials to paint the same scene from a closer spot. Looking to capture the moment, neither artist ignored the yard’s wandering chickens, Manet placing the rooster, hen, and chick as avian counterparts to Monet, his wife Camille, and son Jean. At some point of that day, Monet took a break from tending his flowers to make a picture of Manet painting in the garden.